Problems tagged with "linear transformations"

Problem #09

Tags: lecture-02, linear transformations, quiz-02

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (2x_1 - x_2, \, x_1 + 3x_2)^T\). Is \(\vec f\) a linear transformation? Justify your answer.

Solution

Yes, \(\vec f\) is a linear transformation.

To verify linearity, we must show that for all vectors \(\vec x, \vec y\) and scalars \(\alpha, \beta\):

Let \(\vec x = (x_1, x_2)^T\) and \(\vec y = (y_1, y_2)^T\). Then:

Therefore, \(\vec f\) is linear.

Problem #10

Tags: lecture-02, linear transformations, quiz-02

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (x_1 x_2, \, x_2)^T\). Is \(\vec f\) a linear transformation? Justify your answer.

Solution

No, \(\vec f\) is not a linear transformation.

To show this, we find a counterexample. Consider \(\vec x = (1, 1)^T\) and \(\vec y = (1, 1)^T\), and let \(\alpha = \beta = 1\).

First, compute \(\vec f(\vec x + \vec y) = \vec f((2, 2)^T)\):

\(\vec f((2, 2)^T) = (2 \cdot 2, \, 2)^T = (4, 2)^T\) Now compute \(\vec f(\vec x) + \vec f(\vec y)\):

Since \((4, 2)^T \neq(2, 2)^T\), we have \(\vec f(\vec x + \vec y) \neq\vec f(\vec x) + \vec f(\vec y)\).

Therefore, \(\vec f\) is not linear. (The product \(x_1 x_2\) in the first component makes the function nonlinear.)

Problem #11

Tags: lecture-02, linear transformations, quiz-02

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (x_1^2, \, x_2)^T\). Is \(\vec f\) a linear transformation? Justify your answer.

Solution

No, \(\vec f\) is not a linear transformation.

A quick way to check: for any linear transformation, we must have \(\vec f(c\vec x) = c \vec f(\vec x)\) for any scalar \(c\).

Let us check the scaling property with \(\vec x = (1, 0)^T\) and \(c = 2\):

Since \((4, 0)^T \neq(2, 0)^T\), we have \(\vec f(2\vec x) \neq 2\vec f(\vec x)\).

Therefore, \(\vec f\) is not linear. (The squared term \(x_1^2\) makes the function nonlinear.)

Problem #12

Tags: lecture-02, linear transformations, quiz-02

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (-x_2, \, x_1)^T\). Is \(\vec f\) a linear transformation? Justify your answer.

Solution

Yes, \(\vec f\) is a linear transformation.

To verify linearity, we must show that for all vectors \(\vec x, \vec y\) and scalars \(\alpha, \beta\):

Let \(\vec x = (x_1, x_2)^T\) and \(\vec y = (y_1, y_2)^T\). Then:

Therefore, \(\vec f\) is linear.

By the way, this transformation does something interesting geometrically: it rotates vectors by \(90°\) counterclockwise.

Problem #13

Tags: lecture-02, linear transformations, quiz-02

Suppose \(\vec f\) is a linear transformation with:

Let \(\vec x = (2, 5)^T\). Compute \(\vec f(\vec x)\).

Solution

\(\vec f(\vec x) = (17, -1)^T\).

Since \(\vec f\) is linear, we can write:

Here, \(x_1 = 2\) and \(x_2 = 5\). Substituting the given values:

Problem #14

Tags: lecture-02, linear transformations, quiz-02

Suppose \(\vec f\) is a linear transformation with:

Let \(\vec x = (4, -2)^T\). Compute \(\vec f(\vec x)\).

Solution

\(\vec f(\vec x) = (-8, 10)^T\).

Since \(\vec f\) is linear, we can write:

Substituting the given values:

Problem #17

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (x_2, -x_1)^T\) be a linear transformation, and let \(\mathcal{U} = \{\hat{u}^{(1)}, \hat{u}^{(2)}\}\) be an orthonormal basis for \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with:

Express the transformation \(\vec f\) in the basis \(\mathcal{U}\). That is, if \([\vec x]_{\mathcal{U}} = (z_1, z_2)^T\), find \([\vec f(\vec x)]_{\mathcal{U}}\) in terms of \(z_1\) and \(z_2\).

Solution

\([\vec f(\vec x)]_{\mathcal{U}} = (z_2, -z_1)^T \).

To express \(\vec f\) in the basis \(\mathcal{U}\), we first need to find what \(\vec f\) does to the basis vectors \(\hat{u}^{(1)}\) and \(\hat{u}^{(2)}\), then express the results in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis.

To start, we compute \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\) and \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\).

However, notice that this is \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\) and \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\) expressed in the standard basis. Therefore, we need to do a change of basis to express these vectors in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis. We do the change of basis just like we would for any vector: by dotting with each basis vector. That is:

We need to calculate all of these dot products:

Therefore, we have:

Finally, since \(\vec f\) is linear, we can express \(\vec f(\vec x)\) in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis as:

Problem #18

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (x_1, -x_2, x_3)^T\) be a linear transformation, and let \(\mathcal{U} = \{\hat{u}^{(1)}, \hat{u}^{(2)}, \hat{u}^{(3)}\}\) be an orthonormal basis for \(\mathbb{R}^3\) with:

Express the transformation \(\vec f\) in the basis \(\mathcal{U}\). That is, if \([\vec x]_{\mathcal{U}} = (z_1, z_2, z_3)^T\), find \([\vec f(\vec x)]_{\mathcal{U}}\) in terms of \(z_1\), \(z_2\), and \(z_3\).

Solution

\([\vec f(\vec x)]_{\mathcal{U}} = (-z_2, -z_1, z_3)^T \).

To express \(\vec f\) in the basis \(\mathcal{U}\), we first need to find what \(\vec f\) does to the basis vectors \(\hat{u}^{(1)}\), \(\hat{u}^{(2)}\), and \(\hat{u}^{(3)}\), then express the results in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis.

To start, we compute \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\), \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\), and \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(3)})\).

However, notice that these are expressed in the standard basis. Therefore, we need to do a change of basis to express these vectors in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis. We do the change of basis just like we would for any vector: by dotting with each basis vector. That is:

We calculate the dot products for \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\):

We calculate the dot products for \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\):

For \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(3)})\), we note that \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(3)}) = (0, 0, 1)^T = \hat{u}^{(3)}\), so:

Therefore, we have:

Finally, since \(\vec f\) is linear, we can express \(\vec f(\vec x)\) in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis as:

Problem #19

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Let \(\vec f(\vec x) = (x_2, x_1)^T\) be a linear transformation, and let \(\mathcal{U} = \{\hat{u}^{(1)}, \hat{u}^{(2)}\}\) be an orthonormal basis for \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with:

Express the transformation \(\vec f\) in the basis \(\mathcal{U}\). That is, if \([\vec x]_{\mathcal{U}} = (z_1, z_2)^T\), find \([\vec f(\vec x)]_{\mathcal{U}}\) in terms of \(z_1\) and \(z_2\).

Solution

\([\vec f(\vec x)]_{\mathcal{U}} = (z_1, -z_2)^T \).

To express \(\vec f\) in the basis \(\mathcal{U}\), we first compute what \(\vec f\) does to the basis vectors \(\hat{u}^{(1)}\) and \(\hat{u}^{(2)}\).

Now, these results are expressed in the standard basis, and we need to convert them to the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis. In principle, we could do this by dotting with each basis vector, but we can also notice that:

This means we can immediately write:

Finally, since \(\vec f\) is linear:

Problem #20

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Suppose \(\vec f\) is a linear transformation with:

Write the matrix \(A\) that represents \(\vec f\) with respect to the standard basis.

Solution

To make the matrix representing the linear transformation \(\vec f\) with respect to the standard basis, we simply place \(f(\hat{e}^{(1)})\) and \(\vec f(\hat{e}^{(2)})\) as the first and second columns of the matrix, respectively. That is:

Problem #21

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Suppose \(\vec f\) is a linear transformation with:

Write the matrix \(A\) that represents \(\vec f\) with respect to the standard basis.

Solution

To make the matrix representing the linear transformation \(\vec f\) with respect to the standard basis, we simply place \(\vec f(\hat{e}^{(1)})\), \(\vec f(\hat{e}^{(2)})\), and \(\vec f(\hat{e}^{(3)})\) as the columns of the matrix. That is:

Problem #22

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Consider the linear transformation \(\vec f : \mathbb{R}^3 \to\mathbb{R}^3\) that takes in a vector \(\vec x\) and simply outputs that same vector. That is, \(\vec f(\vec x) = \vec x\) for all \(\vec x\).

What is the matrix \(A\) that represents \(\vec f\) with respect to the standard basis?

Solution

You probably could have written down the answer immediately, since this is a very well-known transformation called the identity transformation and the matrix is the identity matrix. But here's why the identity matrix is what it is:

To find the matrix, we need to determine what \(\vec f\) does to each basis vector:

Placing these as columns:

That is the identity matrix we were expecting.

Problem #23

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Suppose \(\vec f\) is represented by the following matrix:

Let \(\vec x = (5, 2)^T\). What is \(\vec f(\vec x)\)?

Solution

\(\vec f(\vec x) = (8, 23)^T\).

Since the matrix \(A\) represents \(\vec f\), we have \(\vec f(\vec x) = A \vec x\). We compute:

Problem #24

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Suppose \(\vec f\) is represented by the following matrix:

Let \(\vec x = (2, 1, -1)^T\). What is \(\vec f(\vec x)\)?

Solution

\(\vec f(\vec x) = (4, -2, 3)^T\).

Since the matrix \(A\) represents \(\vec f\), we have \(\vec f(\vec x) = A \vec x\). We compute:

Problem #25

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Consider the linear transformation \(\vec f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to\mathbb{R}^2\) that rotates vectors by \(90^\circ\) clockwise.

Let \(\mathcal{U} = \{\hat{u}^{(1)}, \hat{u}^{(2)}\}\) be an orthonormal basis with:

What is the matrix \(A\) that represents \(\vec f\) with respect to the basis \(\mathcal{U}\)?

Solution

Remember that the columns of this matrix are:

So we need to compute \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\) and \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\), then express those results in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis.

Let's start with \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\). \(\vec f\) takes the vector \(\hat{u}^{(1)} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, 1)^T\), which points up and to the right at a \(45^\circ\) angle, and rotates it \(90^\circ\) clockwise, resulting in the vector \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, -1)^T = \hat{u}^{(2)}\)(that is, the unit vector pointing down and to the right at a \(45^\circ\) angle). As it so happens, this is exactly the second basis vector. That is, \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)}) = \hat{u}^{(2)}\).

Now for \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\). \(\vec f\) takes the vector \(\hat{u}^{(2)} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, -1)^T\), which points down and to the right at a \(45^\circ\) angle, and rotates it \(90^\circ\) clockwise, resulting in the vector \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(-1, -1)^T\). This isn't \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\), exactly, but it is \(-1\) times \(\hat{u}^{(1)}\). That is, \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)}) = -\hat{u}^{(1)}\).

What we have found is:

Therefore, the matrix is:

Problem #26

Tags: linear algebra, linear transformations, quiz-02, lecture-03

Consider the linear transformation \(\vec f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to\mathbb{R}^2\) that reflects vectors over the \(x\)-axis.

Let \(\mathcal{U} = \{\hat{u}^{(1)}, \hat{u}^{(2)}\}\) be an orthonormal basis with:

What is the matrix \(A\) that represents \(\vec f\) with respect to the basis \(\mathcal{U}\)?

Solution

Remember that the columns of this matrix are:

So we need to compute \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\) and \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\), then express those results in the \(\mathcal{U}\) basis.

Let's start with \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)})\). \(\vec f\) takes the vector \(\hat{u}^{(1)} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, 1)^T\), which points up and to the right at a \(45^\circ\) angle, and reflects it over the \(x\)-axis, resulting in the vector \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, -1)^T = \hat{u}^{(2)}\)(the unit vector pointing down and to the right at a \(45^\circ\) angle). That is, \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(1)}) = \hat{u}^{(2)}\).

Now for \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)})\). \(\vec f\) takes the vector \(\hat{u}^{(2)} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, -1)^T\), which points down and to the right at a \(45^\circ\) angle, and reflects it over the \(x\)-axis, resulting in the vector \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(1, 1)^T = \hat{u}^{(1)}\). That is, \(\vec f(\hat{u}^{(2)}) = \hat{u}^{(1)}\).

What we have found is:

Therefore, the matrix is:

Problem #36

Tags: linear algebra, quiz-03, eigenvalues, eigenvectors, lecture-04, linear transformations

Consider the linear transformation \(\vec f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to\mathbb{R}^2\) that reflects vectors over the line \(y = -x\).

Find two orthogonal eigenvectors of this transformation and their corresponding eigenvalues.

Solution

The eigenvectors are \((1, -1)^T\) with \(\lambda = 1\), and \((1, 1)^T\) with \(\lambda = -1\).

Geometrically, vectors along the line \(y = -x\)(i.e., multiples of \((1, -1)^T\)) are unchanged by reflection over that line, so they have eigenvalue \(1\). Vectors perpendicular to the line \(y = -x\)(i.e., multiples of \((1, 1)^T\)) are flipped to point in the opposite direction, so they have eigenvalue \(-1\).

Problem #37

Tags: linear algebra, quiz-03, eigenvalues, eigenvectors, lecture-04, linear transformations

Consider the linear transformation \(\vec f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to\mathbb{R}^2\) that scales vectors along the line \(y = x\) by a factor of 2, and scales vectors along the line \(y = -x\) by a factor of 3.

Find two orthogonal eigenvectors of this transformation and their corresponding eigenvalues.

Solution

The eigenvectors are \((1, 1)^T\) with \(\lambda = 2\), and \((1, -1)^T\) with \(\lambda = 3\).

Geometrically, vectors along the line \(y = x\)(i.e., multiples of \((1, 1)^T\)) are scaled by a factor of 2, so they have eigenvalue \(2\). Vectors along the line \(y = -x\)(i.e., multiples of \((1, -1)^T\)) are scaled by a factor of 3, so they have eigenvalue \(3\).

Problem #38

Tags: linear algebra, quiz-03, eigenvalues, eigenvectors, lecture-04, linear transformations

Consider the linear transformation \(\vec f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to\mathbb{R}^2\) that rotates vectors by \(180°\).

Find two orthogonal eigenvectors of this transformation and their corresponding eigenvalues.

Solution

Any pair of orthogonal vectors works, such as \((1, 0)^T\) and \((0, 1)^T\). Both have eigenvalue \(\lambda = -1\).

Geometrically, rotating any vector by \(180°\) reverses its direction, so \(\vec f(\vec v) = -\vec v\) for all \(\vec v\). This means every nonzero vector is an eigenvector with eigenvalue \(-1\).

Since we need two orthogonal eigenvectors, any orthogonal pair will do.

Problem #43

Tags: linear algebra, quiz-03, symmetric matrices, eigenvectors, lecture-04, linear transformations

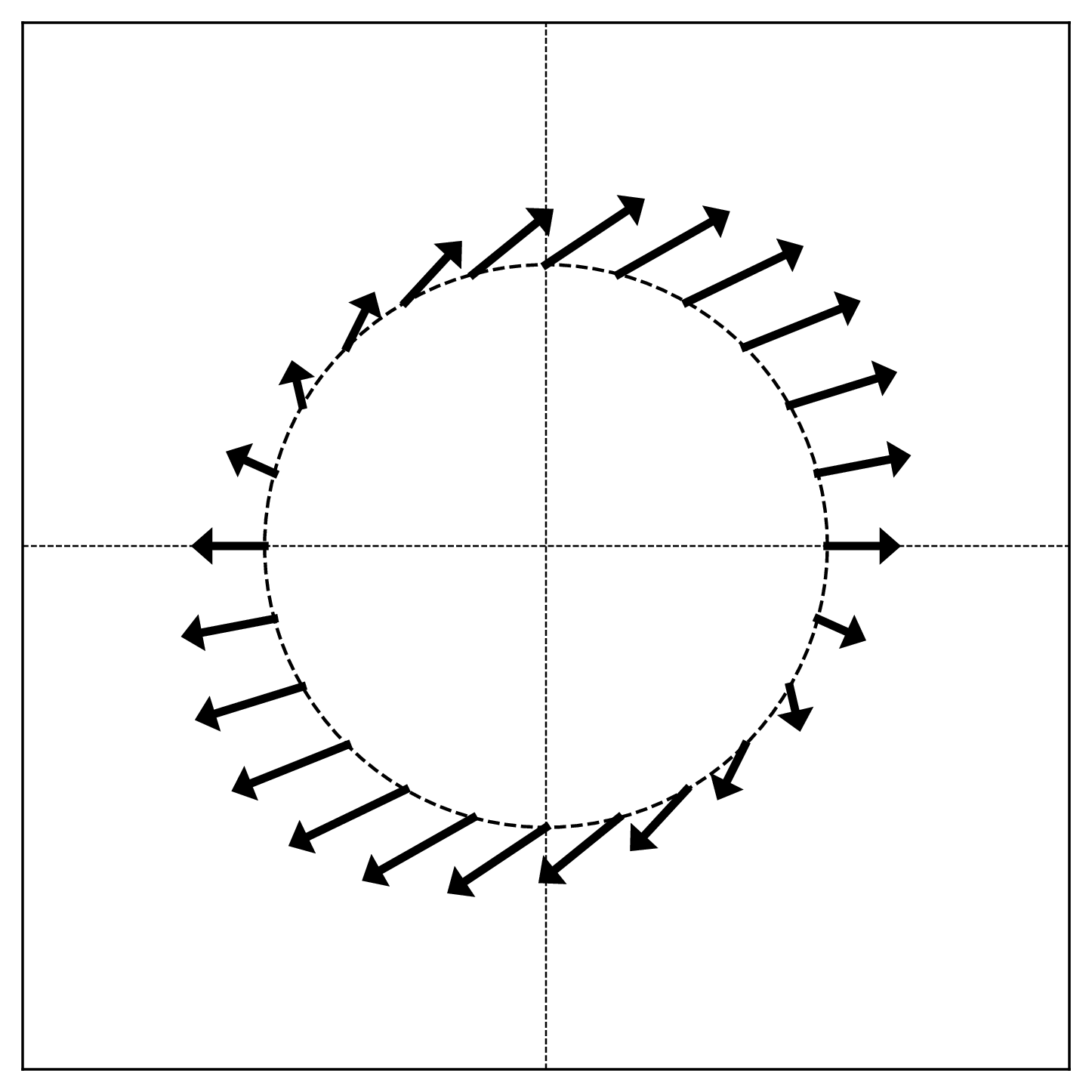

The figure below shows a linear transformation \(\vec{f}\) applied to points on the unit circle. Each arrow shows the direction and relative magnitude of \(\vec{f}(\vec{x})\) for a point \(\vec{x}\) on the circle.

True or False: The linear transformation \(\vec{f}\) is symmetric.

Solution

False.

Recall from lecture that symmetric linear transformations have orthogonal axes of symmetry. In the visualization, this would appear as two perpendicular directions where the arrows point directly outward (or inward) from the circle.

In this figure, there are no such orthogonal axes of symmetry. The pattern of arrows does not exhibit the characteristic symmetry of a symmetric transformation.

Problem #44

Tags: linear algebra, quiz-03, diagonal matrices, eigenvectors, lecture-04, linear transformations

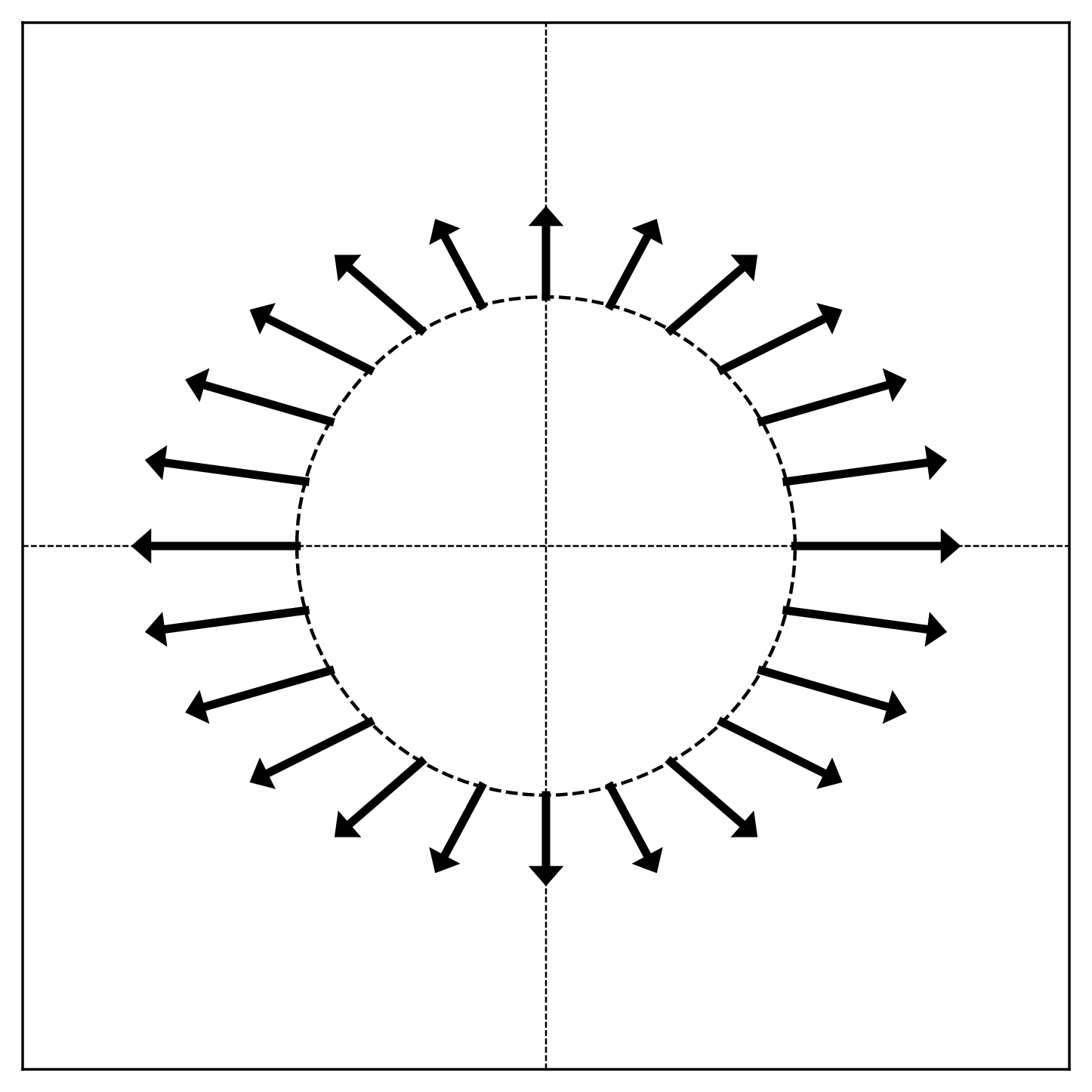

The figure below shows a linear transformation \(\vec{f}\) applied to points on the unit circle. Each arrow shows the direction and relative magnitude of \(\vec{f}(\vec{x})\) for a point \(\vec{x}\) on the circle.

True or False: The matrix representing \(\vec{f}\) with respect to the standard basis is diagonal.

Solution

True.

A matrix is diagonal if and only if the standard basis vectors are eigenvectors. In the visualization, eigenvectors correspond to directions where the arrows point radially (directly outward or inward).

Looking at the figure, the arrows at \((1, 0)\) and \((-1, 0)\) point horizontally, and the arrows at \((0, 1)\) and \((0, -1)\) point vertically. This means the standard basis vectors \(\hat e^{(1)} = (1, 0)^T\) and \(\hat e^{(2)} = (0, 1)^T\) are eigenvectors.

Since the standard basis vectors are eigenvectors, the matrix is diagonal in the standard basis.